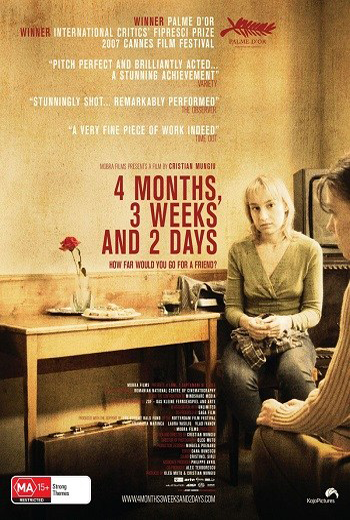

4 MONTHS 3 WEEKS AND 2 DAYS เธอจ่ายมัน..ด้วยชีวิต (2007) พากย์ไทย

หมวดหมู่ : หนังดราม่า

เรื่องย่อ : 4 MONTHS 3 WEEKS AND 2 DAYS เธอจ่ายมัน..ด้วยชีวิต (2007) พากย์ไทย

แนว/ประเภท : Drama

ผู้กำกับภาพยนตร์ : Cristian Mungiu

บทภาพยนตร์ : Cristian Mungiu

นักแสดง : Anamaria Marinca, Laura Vasiliu, Vlad Ivanov

วันที่ออกฉาย : 6 มิถุนายน 2550

IMDB : tt1032846

คะแนน : 7.9

รับชม : 538 ครั้ง

เล่น : 94 ครั้ง

Time is a formidable enemy in Cristian Mungiu’s 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days, and thus it’s appropriate that its scenes, shot in handheld cinemascope, are built around prolonged, pitilessly unblinking takes in which the camera doesn’t always follow the actors, or even wait for them to appear. In the late Eighties, during the waning months of the Ceausescu regime, Otilia (Anamaria Marinca) has pledged to help her roommate, Gabita (Laura Vasiliu), obtain an illegal abortion. The wheels have already been set in motion as the movie begins in their cluttered dorm room, mid-conversation, though we don’t at first see either woman.

The pair’s friendship is close enough that Gabita doesn’t hesitate to make unreasonable demands and Otilia strives to meet them. Intermittently chiding her friend, the latter engages in an increasingly perilous series of transactions that can only sometimes be expedited with black-market Kent cigarettes—including going alone to bring the balding back-alley abortionist Bebe (Vlad Ivanov, in a frighteningly modulated performance) to the hotel where Gabita is waiting. In the harrowing scenes that follow, Marinca, who has the long face of a doe and gives wary, sidelong glances, shows the girlishness beneath Otilia’s serious demeanor being permanently drained away, while the wan Vasiliu embodies feeble desperation. Leaving Gabita to attend a party for her boyfriend’s mother, Otilia must endure sitting at a table so crowded with critical, overbearing adults she nearly disappears among them.

As events slip further from Otilia’s control, the film subtly incorporates elements of a thriller without relinquishing its enveloping realism: a knife slipped into a pocket, a ringing phone unanswered, a man seemingly trailing Otilia through the nighttime streets. Bucharest is an underlit labyrinth where every turn mirrors a choice that must be made—early in the film Otilia makes her way through numerous corridors, but the city itself suggests a network of hallways—and each location powerfully contributes to a sense of alienation. Although the civil authorities play no role in the narrative, the hallway outside the hotel room in which the abortion takes place is a sinister realm filled with blood-red club chairs that seem to await the arrival of unseen officials.

Mungiu’s tale was inspired by an experience recounted by a close friend, and the wretched details of the women’s interactions with Bebe ring true in a way that suggests they could only have been drawn from real life. In 1966, soon after Ceausescu assumed power, a law was passed banning abortion, which had been legal since 1957. Amid poverty and shortages, the regime fetishized maternity, lauding women with large broods and peddling creepy images of “heroic” motherhood. Some estimate that up to half a million women died from illegal abortions before the revolution in 1989. 4 Months doesn’t nurse any infantile nostalgia for the era. Even those wielding authority feel beleaguered, from the sour hotel clerk who wonders when her paycheck will materialize, to the loathsome, aggrieved Bebe.

Mungiu has taken a leap forward into bold, focused storytelling. His first feature, Occident (02), which inventively intertwined stories about financially strapped, conflicted characters adrift in post-Communist Romania, summoned a mood of rueful absurdity but relied too heavily on narrative coincidence, sentimental music, and freeze frames. Collaborating with DP Oleg Mutu he has fashioned a film of rigor and urgency. Mutu also shot Cristi Puiu’s corrosively bleak The Death of Mr. Lazarescu, and though the two movies differ in tone and shooting style, both unfold over a 24-hour period and recount a journey through a grim netherworld. In 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days it is an underground realm marked by perverse rules, where Bebe is a law outside the law, meting out his own capricious punishments. But although Otilia’s ordeal demands the patience of a Kafka protagonist, it cannot be seen as in any way allegorical. When, at the film’s conclusion, she decides to never again speak of what happened, one is reminded that fantasy plays a small part in this wrenching story.